Kenya Celis

Continental Gentrification

Over-tourism in Latin America has plagued the region for decades. But now citizens are not just bonding over their shared disdain for tourists and Airbnb renters, but mobilizing to take their grievances to the streets, elevating the issue to a national level. In various cities across the continent, there have been surges in global tourism and in the number of digital nomads from America and Europe. These foreigners help fuel the economy by increasing the demand for luxury apartments and aesthetic cafes, bringing in their appreciated foreign currency, and providing opportunity for Latin American economies.

Consequently, these developments–while outwardly signaling economic prosperity for landlords, real estate developers, and business owners–have led to augmented rent prices for locals, an influx of nomadic residents, and the effacement of cultural heritage. Major cities in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Peru have already felt the neocolonial effects of these hegemons. Mexico is one of the countries at the forefront of this rapid rise in over-tourism, leading the effort to expel foreign visitors.

Protests in CDMX

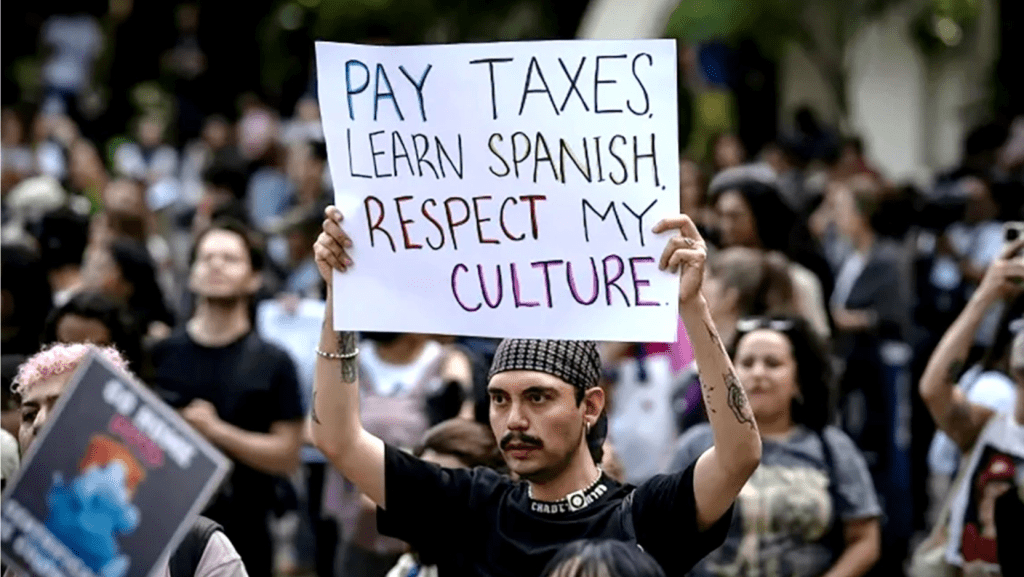

In the last six months, Mexico City (CDMX) has seen an increasing number of protests against exorbitant housing costs and the unwanted influx of tourists due to brought on by the country’s economic dependence.

Protests in the city are nothing new; however, in recent years, displacement and eviction of locals have been happening at an increasingly rapid rate. According to the Inter-American Dialogue, more than 20,000 low-income households are forced out of the city annually due to the lack of affordable housing. This seismic power shift between foreigners and Mexico City locals has only magnified tensions, prompting an aggressive response by citizens during the summer. The July 4th protest, while having the full intention of being peaceful, resulted in crowds getting heated, with radical protestors vandalizing buildings, breaking down doors, and smashing windows of businesses in gentrified neighborhoods, chanting “Gringos Out!”

The attempt at a call to action to the government, which seemed to be profiting from its citizens’ misfortune, did not elicit the response it had hoped. President Sheinbaum took to addressing the protest in a press conference, condemning the “xenophobic” behavior of all Mexican citizens, with little assurance that their concerns would be addressed promptly.

Government Negligence

Mexican citizens attribute the deluge of tourists to the “digital nomadism” and tourism agreement signed by President Claudia Sheinbaum during her tenure as the mayor of Mexico City in 2022. The agreement, which intended to stimulate economic growth by promoting Mexico City as a hub for remote workers, has led to a record number of 47.4 million tourists between January and July 2025, and citizens reaching their tipping point with the housing crisis. The trade-off of implementing these partnership agreements was a vapid response from locals, which fostered animosity toward their ineffective governance.

Officials did not account for the myriad of issues this would cause Mexicans. By overlooking the immediate needs of its citizens and prioritizing only ways to restore the city’s economy post-COVID, the government enabled not just gentrification but also rent inflation and a shortage of housing options in the city.

Between 2010 and 2020, Mexico City had the lowest rate of new houses built per 1000 residents in the country. The lack of new construction, coupled with the overall rise in population, indicates that this isn’t just about tourists gentrifying areas, but the Mexican government’s careless urban planning. Without a comprehensive plan to offset the high concentration of tourists and nomads with affordable housing options, long-term residents remain at risk of displacement.

21st Century Neocolonialism

These trends and patterns are not new to Latin Americans. The global South had become a product of centuries of cultural imposition and resource depletion by colonial powers. Now, these same powers have reemerged in these areas under the guise of bringing in business and boosting the economy.

Citizens in Mexico City have argued that the increased Anglo presence has led to the erasure of their culture, with Atole stands being replaced by Starbucks locations, menus now written in English, and the U.S. dollar overshadowing the Mexican peso.

Current trends mimic the same behaviors as past waves of displacement by neocolonial powers and by old ideas about who gets to live in these Latin American cities and how they should be, rather than accepting them for how they already are.

Deep-rooted inequality already existed in Mexico, dating back to the late 1800s, when ideas of “modernization” and export-oriented trade exacerbated societal inequality, excluding non-elites and working-class individuals from achieving middle-class status. The economic and cultural influence of the US and other foreign powers promoted marginalization of lower-class individuals, relative to what is happening currently.

Now, the strong American presence has created a power imbalance between tourists and locals, where even the wealthiest Mexicans can get priced out by the US dollar and have their cultural identity replaced by trendy restaurants, shops, and rentals designed to appeal to the new demographic. The presence of these global nomads has created parallel societal disparities, relegating Mexico City locals to former roles of submission.

Historically, the neocolonial system was met with strong opposition and a violent overthrow. Given the similarities to today’s social inequality, it is only a matter of time before protests escalate into something more revolutionary if the needs of the vulnerable population are not earnestly met.

Not So Rapid Regulation

In response to protests, the mayor of Mexico City promised to develop a 14-point plan to regulate rent prices and hold landlords accountable for their tenant obligations. Yet for reform to be effective, it will need to account for much more than the inflated rent. The effects felt by Mexico City locals stem from a variety of neglected issues in the city. Short-term rental properties outnumber long-term rental options; the construction of new housing lacks incentive; and the de facto dollarization in real estate transactions adds extra challenges to the already pressing issue, requiring any reform plan to address these areas more extensively.

In the meantime, the favored neoliberal economic system continues to reign supreme, and other Latin American countries face a similar fate. In a region already grappling with immense income inequality and challenges to social mobility, the fight against the US dollar is a losing battle. While Mexico tolerates this immigration from its hemispheric hegemon, the gentrification of culturally significant neighborhoods, eviction of locals, and ousting of local businesses continue to intensify. Citizens continue to grow enraged with their government and desperate for reform that doesn’t just cap rent prices but increases mobility for all citizens.

In such a dire time when residents require an immediate solution, the skeleton of a 14-point plan doesn’t offer much hope of salvation. In the coming years, we will see greater displacement of people with generational roots in Mexico City if the government fails to address the underlying causes and institutional fragmentation.